To walk the fields of wheat and barley is to be enveloped in the promise of a prosperous, nourishing bounty. While the endless rows of cereal grass sway uniformly to the rhythms of the Autumnal wind, we are once again invited to bask in a haze of gold and festivity. The harvest season is my favourite time of the year and though it may not be as prominent in comparison to other seasonal celebrations, albeit a result of agricultural progress that has removed most of us from the fields; the magic of the Harvest home endures.

It reverberates with a timeless necessity for us to be in connection with the land. It reminds us to take a moment and relish in all that we have cultivated throughout the year while simultaneously asking us to be appreciative for the gifts of the reaping. For the ease of modernity and our everyday trips to the supermarket would not be possible without the backbreaking labour and calloused hands of those who came before us. Those who gathered to collect the earths produce and to stave off the whispers of hardship from the approaching winter. While we sometimes neglect to be mindful about what we have or fail to embrace more simple pleasures, it is imperative to always honour the core lesson of the harvest which is the need for fellowship. At the heart of the harvest will always be the people; those bonds of family and friends that form the life source of the collective where the songs of the land can be heard, and the great feasts can be held to reinforce solidarity within our communities. Through this, the spirit of hope remains ever present for better days ahead. However, when traversing the beliefs of the harvest, it becomes more apparent that our communities were not always composed of flesh and blood alone.

In fact, many beliefs and customs birthed during the harvest revelry are inextricably linked to the Otherworld where the ragged, terrestrial spirits of the crop watch the sweep of the sickle with bated breath. Some were known to be more benevolent than others such as the spirit of the last sheaf. Known by a variety of names in Britain including the Witch, the Mare, the Mother etc depending on which environment it found itself within, this particular spirit took residence within a spiral receptacle know as a corn dolly which bestowed blessings and fruitfulness on the farmer who gathered her. Other spirits, however, were fashioned with a more mischievous demeanour, waiting to scare off any unsuspecting locals who failed to respect the boundary line. Within an early agrarian society where this belief became more prevalent, it was only a matter of time before these spirits spilled forth from the grain to creep into the dark to prey on the fears of both children and adults. While we have lost some aspects of the propitiatory nature of old-time harvest rituals, replacing the honouring of the land with the arrival of machinery, those spirits still linger. But rather than being forgotten, they have folklorically tethered themselves to a more tangible relic of a bygone age which to this day continues to infatuate our curiosity. This is no other than the iconic Scarecrow.

The scarecrow is a perplexing figure within folk belief. Many would assume they are nothing more than a straw filled decoy, erected to guard the fields from any pesky bird. But while it confers with the flowers and consults with the rain, the scarecrow has undergone significant evolution, with their very being held together with stitches of nostalgia for the rural by each generation who utilises them for their protective virtue. Their simplicity is their greatest asset; able to be constructed in a variety of ways but each just as important as the next in holding the sacred connection between farmer and nature.1 They stand as stoic defenders, ageless to the changing landscape yet always observing and standing to attention as a witness to those scorching sun lit days and bitter, frosty nights. But to be in the company of a scarecrow is to feel a sense of unease creep up inside; a feeling that you’re not quite alone and should be on guard against the empty eyes that seem to follow you along your path.

For millennia scarecrows have been employed around the world to preserve the produce with the first originating 3000 years ago in Ancient Egypt. These were placed along the Nile but lacked the traditional anthropomorphic form due to being constructed from wooden frames covered in netting.2 This allowed the farmers to hide underneath and to capture any wandering quail. On the other hand, the Ancient Greeks preferred to place wooden figures of the God Priapus amongst their fields and vineyards. As the son of Dionysus and Aphrodite, Priapus was revered as a God of Horticulture and fertility, whose physical qualities, including his rather large, virile member, contributed to an abundant harvest and its protection. Priapus later found occupation in Roman belief during their military conquest across Europe, allowing for the God’s image to spread and be intimately connected to the untamed, primal cycles of nature.

In addition, Japanese farmers also began to construct their own type of scarecrow to guard their rice plantations which involved the stacking of rags mixed with the remnants of meat and fish. This would then be subsequently burnt to drive off any animal visitors, earning them the name of Kakashi which translates to bad odour, but this later stuck as the term to mean scarecrow.3 Across Britain and Europe during the Middle Ages the role of the scarecrow was fulfilled by young children, tasked with patrolling the fields and scaring away birds by making loud noises and throwing stones.4 However, this tradition later faded out upon the arrival of the plague in the 14th century, forcing landowners to employ the use of a straw based effigy, adorned with a turnip for a head in the hopes that it would achieve the same affect. Bearing in mind turnips were used for carving before the introduction of the pumpkin, its easy to see how this root vegetable, associated with keeping evil spirits away, should then give rise to the lore of the Jack o lantern and adopt the image of the scarecrow in local story telling when used as its head.

When we look to the various names given to the scarecrow, we can discover a whole range of folkloric entities who harbour amongst their tattered clothing. Within Scotland and the Northern regions of England, scarecrows are sometimes referred to as a Bogle, Boggle or Tattie Bogle; a name associated with a variety of spectral creatures who delight in terrorising unwary humans. A similar term can also be found in the counties of Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Derbyshire which is the infamous Boggart. Folklorist Simon Young describes the Boggart as “Any ambivalent or evil, solitary, supernatural spirit” 5 which can appear in a multitude of ways with sources recounting Boggarts as headless apparitions, hobgoblins, devil like entities, terrifying hounds, or giant sheep, to name a few examples. Boggarts are traditionally known for their destructive tendencies and pranks but were also viewed in a kinder light with the Boggart also being associated with the household spirit; a helpful or a hindering entity who would often be dressed in rags and assist with domestic tasks in exchange for milk left by the hearth. Both Bogle and Boggart, along with other regional variations including Bogy, Bugbear and Bogeyman all share an etymological link to the middle English word Bugge which refers to frightening entities as well as the traditional scarecrow. We can see this link clearly in the postcard illustration by Randolph Caldecott from 1914 which depicts three huntsmen approaching a scarecrow referred to as a Boggart.

Across Wales and my home in the Welsh Marches, the tradition of naming scarecrows after folkloric creatures continues with scarecrows commonly referred to as Bwgan Brian, with Bwgan meaning to scare. The word Bwgan as well as its variant Bwbach are also one of the many names given to the household spirit or fairy in Welsh belief. In my home the Bwgan would usually come out at night when everyone in the house was asleep to complete these tasks but by no means were they bound by the night and if you were caught being lazy, untidy, or too Christian in nature, they would soon find a way to make your day terrible. Most of the time they were perceived as a small and hairy human like creature, but the Bwgan could sometimes transform itself into a cricket which would bring luck to the household as long as it was not killed by the inhabitant. Yet, this tutelary spirit later became synonymous with the Devil and used to as a threat to invoke fear in misbehaving children in the same manner as the scarecrow who’s primary concern is to scare.

In the modern day, the scarecrow has once again adapted to the needs of the people including its participation in local scarecrow festivals. Head to your local village during Autumn and you’ll find a scarecrow around every corner, peaking over the hedge or guarding a driveway, designed in different manners by each household. This vibrant tradition was conceived by Jean Thomas, a member of the Urchfont Village Hall Management committee. Though this may not be frightening scarecrow of folklore, it is nevertheless a testament to its ability to bring the community together to celebrate the harvest season. But this shouldn’t mean we should get too comfortable as many people are still inclined to believe there is something strange about them. An arm has moved out of position one day, or their head was facing the other direction a minute ago or strange footsteps can be heard outside at night. Perhaps the scarecrow hasn’t quite forgot its spectral lineage in the modern day, and neither should we.

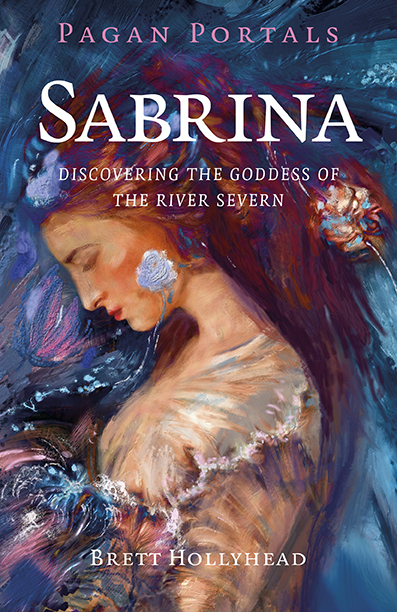

Brett Hollyhead, also known as the Witch of Salopia across social media, is a practicing Welsh Marches Folk Witch, workshop leader and a public speaker at regular Pagan related events/ conferences throughout the United Kingdom. He’s a member of the Cylch y Sarffes Goch Coven (Circle of the Red Serpent) alongside Mhara Starling and Moss Matthey. He’s also a member of OBOD and a guardian of the Doreen Valiente Foundation.

For more details: https://www.collectiveinkbooks.com/moon-books/authors/brett-hollyhead

References

- , K., Kao, R., & Hernick, J. (2019). The Scarecrow as an Indicator of Changes in Cultural Heritage of Rural Poland. Sustainability, 11 (23), p. 6857.

- Abdelhakim, W. M. (2020). Scarring Birds: The concept of the Scarecrow in Ancient Egypt. International Journal of Hertiage, Tourism and Hospitality, 14(2), pp.42-51

- Dugan, E. (2005). Autumn Equinox: The Enchantment of Mabon. Llewellyn Publications

- Ibid

- Young, S. (2022). The Boggart Sourcebook: texts and memories for the study of the British Supernatural. (p. 7). University of Exeter

Leave a comment